Spomenik. In the language of the former Yugoslavia this word means monument, or memorial. To be grammatically correct, the plural should be “Spomenici”, but I have taken some artistic license by writing “Spomeniks”.

These monuments or memorials commemorate the Second World War, but before talking about them, a brief historical reminder is in order.

The military conflict in the Balkans began in April 1941 when the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis forces: Germany, Italy, Hungary and Bulgaria. The land was then divided up and annexed by these different countries. Two independent states, puppet regimes, were created: Croatia with its fascist Ustaše movement and Serbia with its Chetnik equivalent. Faced with oppression from these different powers, a resistance movement was born and a guerrilla group formed. Led by the communist Partisans commanded by Josip Broz, better-known as Tito, this guerrilla war went by the name of the People’s Liberation War or National Liberation War. With the help of the Allies and notably the Soviets, Tito dominated the Axis forces and the conflict came to an end in May 1945. Following this, he created the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, renamed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1963. In 1991, three of its federal republics declared their independence, Croatia, Slovenia and Macedonia, followed by Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1992. All that remained then were Serbia and Montenegro who proclaimed the constitution of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. After many years of conflict, this new entity ceased to exist and in 2003 became the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro which in turn separated in 2006 following Montenegro’s proclamation of independence.

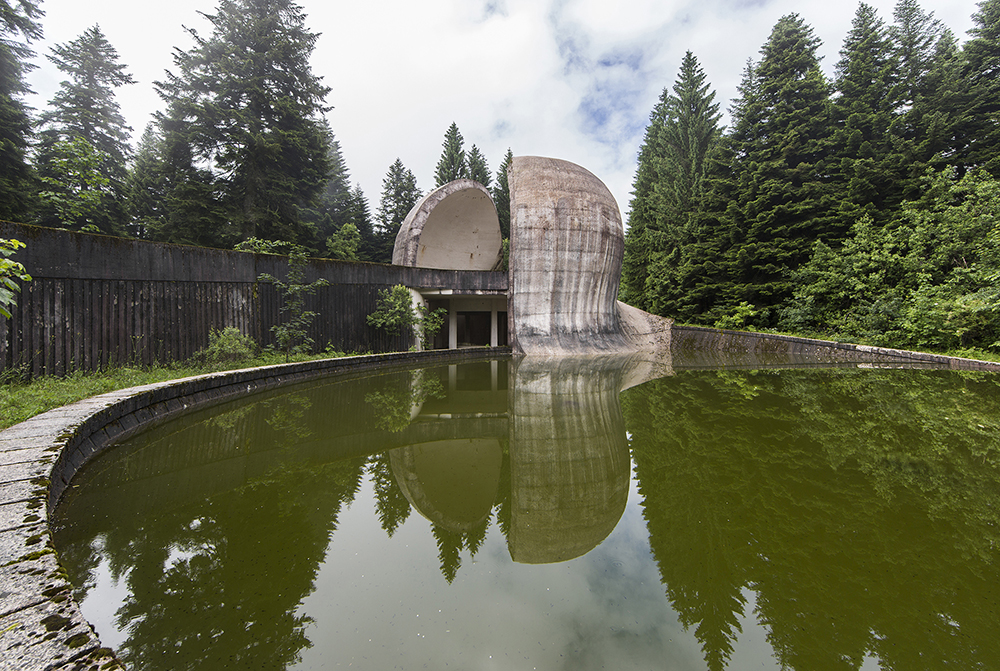

The monuments were mainly built in the 1960s/70s during Tito’s regime, who furthermore, inaugurated a certain number of them himself. They were often erected on the sites of important battles, massacres or concentration camps.

In the majority of cases, their construction was ordered by local communist parties in honour of the communist resistance and the Partisans of the Jugoslovanska ljudska Armada (Yugoslav People’s Army), as well as members of the resistance and local civilians who had lost their lives during the conflict. Very often, local architects were commissioned.

These Spomeniks can come in the shape of an isolated sculpture, or be part of parks or memorial complexes including tombs, crypts or ossuaries that still contain the remains of the people they commemorate. There were thousands of them, scattered across Yugoslavian territory. In the 1980s, they attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors every year, in particular “young pioneers” for their communist and patriotic education.

Today, around thirty years after the breakup of Yugoslavia, most of them have been demolished. Among those still visible, some are in perfect condition and are part of official complexes, some are looked after to a greater or lesser extent, and others have clearly been abandoned or are even in ruins.

When Yugoslavia was broken up, the majority of the monuments suffered from local ethnic conflicts which are partly responsible for the vandalism they have endured. The Bratunac monument for example, which stands on what is now Bosnian soil, was designed by a Serbian architect. Today, it is covered in graffiti, not just on the structure itself but also the adjacent commemorative stones. The same goes for the monument at Mitrovica, designed by a Serbian architect and which is today in Kosovo. Others have met with the same fate simply because they are geographically isolated which has allowed vandals to deface them without being disturbed. And finally, these isolated locations, coupled with a metal structure or covering, make them interesting targets for thieves on the lookout for steel or aluminium. This is why the Sanski Most memorials in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and in particular Petrova Gora in Croatia, or Gevgelija in Macedonia, are nothing more than shadows of their former selves.

Nevertheless, certain monuments still play an important social role. They are the site of annual commemorations, ceremonies, where wreaths are placed in honour of fallen soldiers, but also more surprisingly a meeting place for local inhabitants. I’m mainly thinking here of the Bubanj Memorial Park, at Niš in Serbia where a lot of people come to walk or even picnic on the grassed areas at the foot of the monument. More impressive still, the Banj Brdo Memorial in Banja Luka, Bosnia-Herzegovina. Located at the top of a hill, the road leading up to the memorial is closed off to cars and you have to climb a four kilometre-long slope to reach it. I came across hundreds of people on this road, which is rather badly maintained and now looks more like a pathway. Families go to have a stroll and joggers run. There are pieces of gym apparatus all along the track so you see a lot of people doing sport there too. Once at the top, some even climb the monument itself to chill out in the sunshine.

I am a photographer who is passionate about abandoned places and I travel all across the world to find them. I discovered the Spomeniks when preparing a trip to the Balkans. As some of them have been abandoned, they showed up in my research. I fell in love with them straightaway. And so I carried on looking for abandoned places but also for Spomeniks, whether they had been abandoned or not. I found loads of them and in the end they accounted for almost half of the places I visited during my first trip in 2016. During this journey, I covered 5500 km, across what are today Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Croatia, Kosovo, Montenegro, Macedonia and Slovenia and I photographed 21 Spomeniks. This trip was a revelation for me. I had already sensed the power of these monuments during my research but to see them with my own eyes was far more intense. Indeed, I have always been attracted to abstraction in architecture and these monuments are the quintessential examples. Some of them, with a futurist design, are just simply incredible. By adding a Brutalist aspect, concrete, to these sometimes immense structures, something very powerful is created. With a highly-charged historical background, the result is no longer just powerful but unique. Some less abstract monuments also have a very strong symbolism. The most common symbol is the flower used notably at Jasenovac, Podhum, Zaostrog, Gevgelija, Gligino Brdo and Grmeć.

This flower represents renaissance, life, and is undoubtedly the strongest symbol when you take into account that these monuments were built in the wake of the deadly Second World War. To see them in real life reinforced the idea that I should dig deeper and return to the Balkans. And so I did some more research and went back there in 2017. This time I travelled 4500 km across the same countries, but Albania too. I visited 29 Spomeniks during this trip as well as many abandoned places.

I am an adventurer and these two road trips turned out to be something of a treasure hunt for me. Some proved very difficult to find even with Satnav co-ordinates. I didn’t just limit my trips to driving, photographing, driving, photographing. Certain monuments were located in very out of the way areas and driving was sometimes an adventure in itself. And so I covered dozens of kilometres of trails. And sometimes, where the trail ended, I had to continue on foot for a while, virtually hiking. Here, I’m thinking specifically about the monument at Gevgelija where the surrounding area has been completely destroyed over several kilometres due to a project for a motorway. Others are even located in zones where there are still landmines (Novi Travnik for example).

My aim with this book is to finalise a photographic project, but it would be a shame to limit it just to a succession of photos. And so I wanted to give these monuments some historical context, accompany them with information as far as it was possible. Despite some in-depth research into the specific history of each one, it has sometimes been difficult or even impossible to find this information, even things as simple as the name of the architect or the year its construction ended. And so some information is missing for certain monuments. I invite readers to write to me if they know anymore. What’s more, most of the data I have managed to collect has come from public encyclopaedias, although a significant part has also come from the translation of news articles from languages such as Slovenian, Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian, and Macedonian, sometimes written in Cyrillic script… These translations have not always been easy and I would like to apologise if some points are inaccurate or incorrect. Lastly, some of the monuments commemorate important battles or events from the Second World War and several pages could be written about them. This is not the object of this book, and so I would suggest that history fans delve deeper into this passionate subject to find out more.

Now, I’ll let readers discover these wonders, the result of my two treasure hunts, for themselves.

Bon voyage in the Balkans, bon voyage into the past but also the future.

NB: The slider below contains one shot of each monument shown in the book where they are presented with name, location, and detail shots along most of the times with architect name, year of completion, historical background and symbolism when available.